3D printers

High quality 3D printers

25% discount on your first order of 3D printed components!

SAVE DISCOUNT NOW!

The perfect symbiosis of quality and quantity!

Complex geometries with ideal properties!

High-resolution components with a wide variety of materials!

High-performance components with sustainable production!

A wide range of materials and ultra-fast production!

Ideal for a wide range of dental indications!

The process from simple component to product!

Fully automate your production!

Fast processing and successful management!

Sorry, there are no results for this combination of filters. Choose another combination of filters.

To ensure that all requests are handled promptly and completely, we ask that you submit all support requests through our support portal.

To the service portalDo you need assistance with your project, do you need advice or a sample part that we can send you?

Send Email

Since its development in the early 1980s in Japan, expanded polypropylene (EPP) has become a mainstay in many high-performance industries. Whether it be the automotive, aerospace, construction or many other industries, EPP is now undoubtedly the material of choice for components that require outstanding impact resistance and energy absorption while also being lightweight.

In particular, EPP has been able to assert itself against EPS, expanding polystyrene, better known under the trade name Styrofoam®, for these high-performance applications. Thanks to its improved impact resistance, recyclability and design flexibility, EPP can be used in many more areas than just those mentioned above. In particular, EPP has been able to assert itself against EPS, expanding polystyrene, better known under the trade name Styrofoam®, for these high-performance applications. Thanks to its improved impact strength, recyclability and design flexibility, EPP is able to open up more and more fields of application compared to EPS, which is supported by the prediction of a compound annual growth rate of the EPP market of 7.21% by 2029.

Traditionally, EPP is formed using metal moulds, for example made of tool steel or aluminium. However, these conventional moulds have a number of disadvantages that increase costs and production time.

Meanwhile, filament 3D printing, also known as FDM or FFF 3D printing, offers the possibility to overcome these disadvantages. In this blog post, I would like to introduce the process of EPP moulding, discuss the advantages of 3D printing for mould making, and show the ideal materials and printing equipment for this process.

The EPP comes in the form of very small beads, which are first ‘pre-expanded’ for a few hours in a steam chamber or with a blowing agent, after which the now slightly larger beads are left to rest for between 12 and 48 hours. This process determines the cell structure of the beads and gives EPP its characteristic properties.

In the next step, the mould is used. This consists of two mould halves, one male and one female, with a cavity that matches the shape of the end product. The EPP beads are now transferred into this mould cavity and clamping force is applied to the two mould halves to hold them evenly together throughout.

Next, steam with a temperature between 100 and 150 °C is introduced into the mould cavity. This steam not only softens the surface of the beads, but also facilitates the further expansion of the material.

To ensure that the steam is distributed evenly within the mould and that the supply of air and removal of steam is controlled, the moulds are equipped with porous structures at certain points to ensure ideal circulation.

After some time under the influence of steam, the surfaces of the beads are so soft that they merge with the surfaces of the surrounding beads. This results in a continuous, monolithic foam structure, while the material continues to expand at the same time, while the cell structure of the material and thus the characteristic properties are retained.

Once the EPP has hardened in the shape predetermined by the cavity, the clamping force is maintained for a short time on the two mould halves while the foam cools slowly. Once it has cooled completely, the clamping force is removed and the finished part is removed from the two mould halves. The moulding process itself, excluding cooling time, takes only a few minutes.

If necessary, the foam can now be finished using a variety of post-processing methods. From cutting to size and surface finishing to colouring – the possibilities for post-processing are almost endless.

The focus is, of course, on the mould in the EPP moulding process, also commonly known as steam chamber moulding. 3D printing is ideally suited to the production of these moulds, as it solves many of the bottlenecks associated with metal production.

First of all, one of the main focuses for any production – costs. Since the EPP mould requires special properties, such as high heat resistance, only special high-performance materials are suitable for 3D printing. The material costs alone are initially higher than for traditional semi-finished metal products – however, this cost disadvantage is not only offset by the processing costs, but more than compensated for, resulting in a significant overall reduction in total production costs of 40% on average.

This is mainly because the porous structures required in the mould do not have to be milled or lasered at great expense, but can simply be integrated into the design in the digital model, allowing the 3D printer to print the finished mould directly with the porous structure. With the appropriate software, the structure can even be precisely adapted to change the surface density of the subsequent EPP part. In addition, the direct integration of these porous structures avoids material waste, which saves both costs and the environment.

Another key factor for any production is time – and here, too, 3D-printed EPP moulds can outperform their traditional counterparts. Since the moulds can vary greatly in size, it is difficult to make an exact comparison, but on average, 3D printing can save about 60% in production time.

But 3D printed moulds save time not only in production time, but also in the moulding process. Since the materials suitable for this application all have excellent insulation properties, no heat is lost during the moulding process, which can reduce cycle time by up to 34%. In addition, much less steam is required, about 65%, which once again lowers costs.

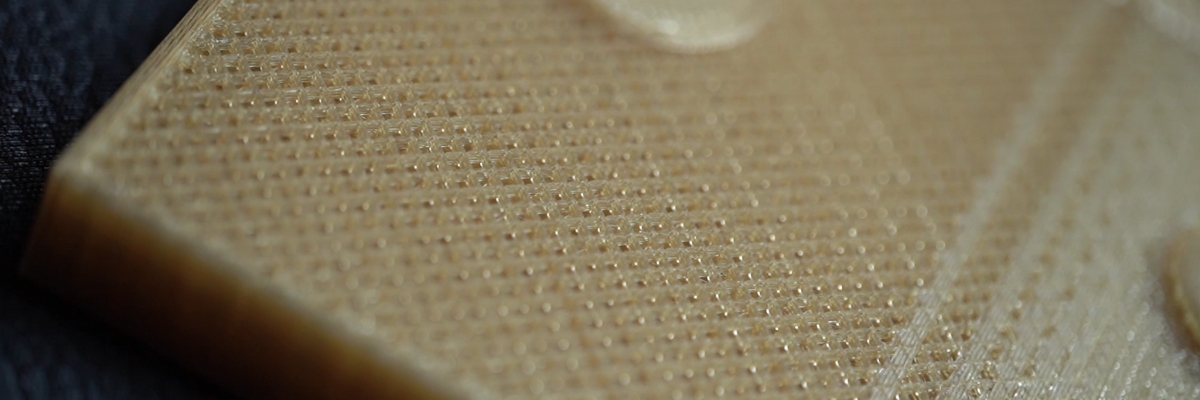

The final major advantage of 3D-printed moulds is the texture quality of the EPP part. Despite the fusion of the individual EPP beads, the final part still has a ‘bead-like’ surface texture – anyone who has ever held Styrofoam® in their hands is familiar with this structure. While this structure is irrelevant for applications such as packaging material, there are many applications where the foam surface needs to look more appealing, which can only be achieved with conventional moulds by post-processing.

However, 3D printing allows the moulds to be printed directly with a texture that is transferred to the EPP part during the moulding process. Furthermore, small features, such as lettering or logos, can be integrated into the digital model with a high level of detail and little effort so that they can also be transferred directly to the foam.

Now that we have discussed the many advantages of additive manufacturing for EPP moulds, we must of course also highlight the downside – after all, there would be no advantages without at least one disadvantage.

This one disadvantage of 3D-printed EPP moulds is their lifespan, which is shorter than that of conventional metal moulds. Of course, an exact lifespan depends on the process circumstances, but on average, a mould can be used to produce at least 2,000 parts before the mould starts to affect the quality of the EPP part.

However, this number can be increased with a few process changes. On the one hand, the advantage of needing less steam should actually be utilised, since a higher steam concentration damages the mould over time. On the other hand, care should be taken to keep the clamping force as low as possible so as not to unnecessarily strain the component.

If these points are observed, the number of EPP parts produced with a single mould can increase to over 5,000. This figure still lags behind that of metal moulds, which can last from 10,000 with aluminium to 1,000,000 with tool steels – although the material and manufacturing costs for tool steels are of course even higher than for aluminium.

Therefore, despite its many advantages, 3D printing is not suitable for very high-volume production. However, for industries that tend to produce small to medium-sized series, or that require frequent adjustments to the mould, 3D printing is all the more ideal.

As mentioned earlier, the materials used require special properties, including high heat resistance, a low coefficient of thermal expansion and outstanding corrosion resistance. Biocompatibility can also be an advantage if the foam could later come into contact with medication or food. This, of course, immediately eliminates standard materials such as PLA or ABS from the selection process.

Our preferred options for manufacturing EPP moulds are composite materials, such as Nylon12CF from Stratasys®, or PEI, better known under its trade name ULTEM™.

We specifically use ULTEM™ 1010 as our workhorse for 3D-printed EPP moulds. With a heat deflection temperature of 214 °C, excellent corrosion resistance, biocompatibility and tensile strength, this material is ideally suited for the additive manufacturing of EPP moulds.

Since this material requires a high processing temperature, highly industrialised systems are needed to process it precisely. Our choice is the F900™ from Stratasys®.

This printing system not only impresses with its ability to process ULTEM™ 1010 with ease, but also with its leading precision and repeatability, as well as its ability to produce almost isotropic components. This ensures maximum service life of the moulds and easy reproduction.

Additive manufacturing is truly no longer a new technology. However, since its conception in the 1980s, new industries and fields of application have been constantly being opened up – and this is now also the case with the production of EPP moulds, which has been made possible primarily by advances in material properties.

This still relatively young application has already left a large footprint. Several major foam manufacturers have already embraced 3D printing, and I hope that this blog post will help to further establish the advantages of additive manufacturing in this industry.

If you have any further questions about this application, please feel free to contact our experts. We will be happy to help you find the right solution for integrating additive manufacturing into your production – whether directly with your own system or by producing as a service provider.

Thank you for reading – and see you in the next blog post!

Cookie settings

We use cookies to provide you with the best possible experience. They also allow us to analyze user behavior in order to constantly improve the website for you. Privacy Policy