3D printers

High quality 3D printers

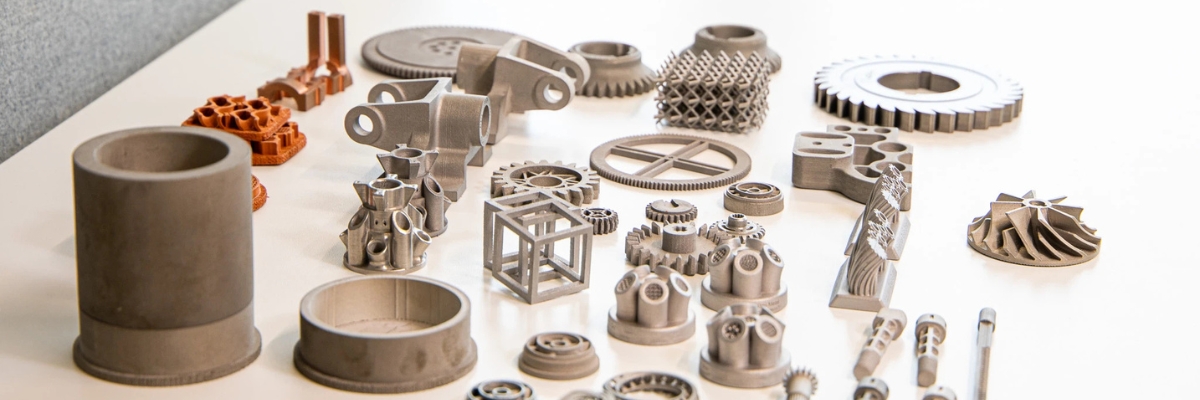

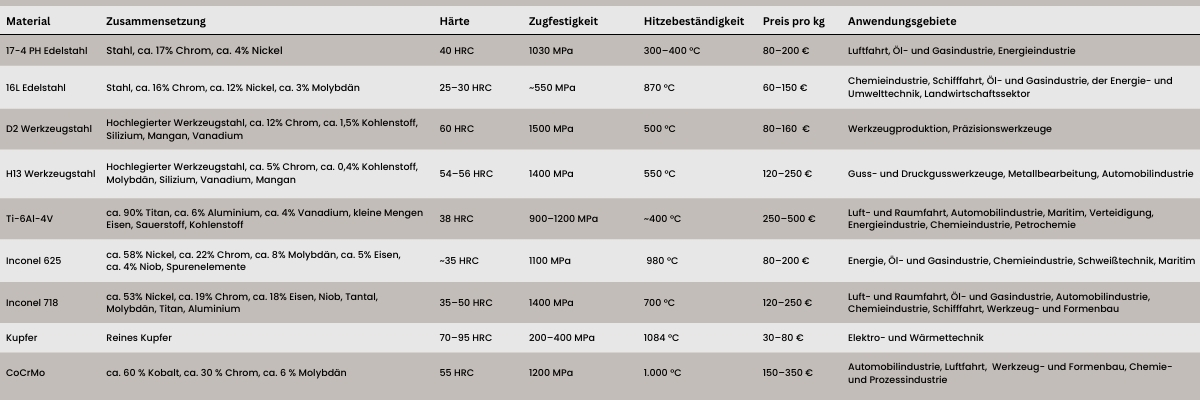

Compared to plastic-based methods, metal 3D printing is still relatively young. Having emerged in the late 1990s and entered commercial use in the mid-2000s, it has since evolved to include an impressive range of alloys that can now be processed through additive manufacturing.

Today, the well-established subcategories of metal 3D printing — which operate using laser, binder, or extrusion technologies — stand out for their virtually unlimited design freedom, isotropic microstructure, and excellent suitability for series production, regardless of the material used.

In this blog post, however, we will focus specifically on the materials themselves and their distinct properties — mechanical, thermal, physical, and chemical — which enable their versatile use across numerous industries and applications.

We categorize these materials into two main groups: first, steel-based alloys, which include stainless and tool steels; and second, special alloys, where we will examine copper-, nickel-, titanium-, and cobalt-chrome-based compositions.

Steel is one of the most versatile construction materials, and its global production volume exceeds that of all other metallic materials combined by more than tenfold. It is therefore unsurprising that steel-based alloys now represent a significant share of metal 3D printing.

In this section, we examine the four most commonly used steel-based alloys: 17-4 PH stainless steel, 316L stainless steel, D2 tool steel, and H13 tool steel — beginning with the stainless steel renowned for its exceptional strength.

17-4 PH is a martensitic stainless steel alloy, whose main constituents, in addition to steel, include approximately 17% chromium and around 4% nickel — hence the designation 17-4. The abbreviation “PH” stands for “Precipitation Hardening,” which describes the specialized heat treatment that imparts the material’s characteristic properties.

This stainless steel is particularly noted for its high strength and moderately high hardness, making it highly popular in a wide range of applications. Following the appropriate heat treatment, 17-4 PH can achieve a tensile strength of up to 1,030 MPa, and hardness can reach up to 40 HRC (Rockwell C).

Another advantage is its good corrosion resistance, which depends on factors such as salt concentration and temperature, the presence of other chemicals, and mechanical stress. In addition, 17-4 PH is highly weldable and relatively easy to process.

However, 17-4 PH has limitations at elevated temperatures. The material remains stable only within a range of 300 to 400 °C, which is significantly lower than the heat resistance of many other metals used in 3D metal printing. Furthermore, 17-4 PH is relatively expensive, with prices ranging from €80 to €200 per kilogram, and post-processing can be challenging due to its high hardness and strength.

A key application area for 17-4 PH is the aerospace industry. The combination of high strength and good corrosion resistance makes the alloy ideal for components such as structural brackets, hydraulic cylinders, and pistons.

Additionally, 17-4 PH is used in the oil and gas sector, for example in drilling tools, pump components, or additively manufactured valves. In the energy industry, the alloy is employed for parts such as rotors and bearings in steam turbines.

316L belongs to the austenitic class and is composed primarily of steel, with approximately 16% chromium, around 12% nickel, and about 3% molybdenum. The “L” in 316L stands for “Low Carbon,” as the carbon content is limited to a maximum of 0.03%.

The outstanding property of 316L is its high corrosion resistance. Due to its elevated chromium and nickel content, along with the molybdenum addition, the material is particularly resistant to salt and seawater, chloride-induced corrosion, as well as various acids and alkalis. The low carbon content further protects against intergranular and crevice corrosion.

Additionally, 316L is highly weldable. It can withstand temperatures up to 870 °C, offers moderate hardness of 25–30 HRC, and is relatively affordable, with prices ranging between €60 and €150 per kilogram. In 3D printing, 316L is easily processed, and post-processing is simpler due to its lower hardness.

In terms of strength, however, 316L cannot match other steel-based alloys. Its tensile strength is approximately 550 MPa, making the material prone to deformation or cracking under high loads. Moreover, ductility decreases at very low temperatures, increasing brittleness and limiting certain applications.

One area where 316L excels is the chemical industry. Here, the material’s corrosion resistance and moderate hardness make it ideal for applications such as piping, pumps, valves, tanks, and condensers.

316L is also widely used in maritime applications, for example in corrosion protection systems. Other significant application areas include the oil and gas industry, energy and environmental technology, and agriculture.

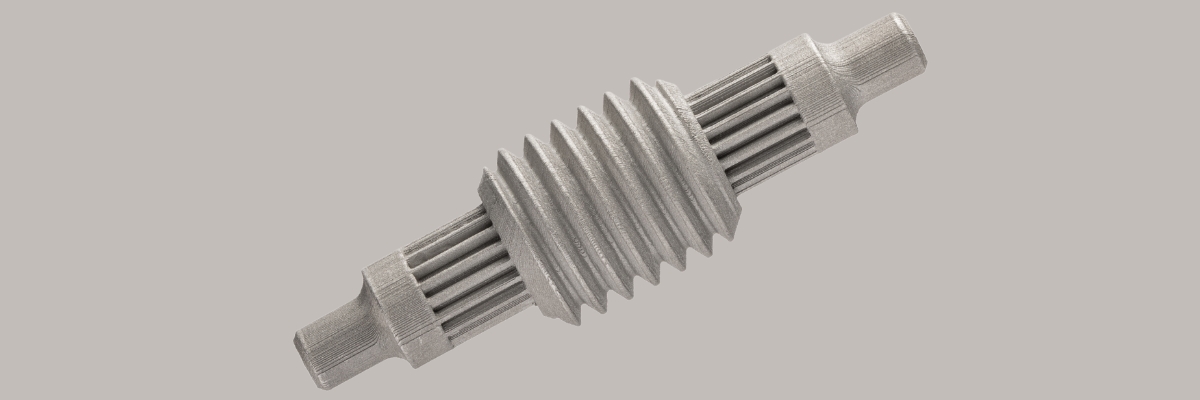

D2 is a high-alloy tool steel with a high chromium content of approximately 12% and a carbon content of around 1.5%. It also contains elements such as silicon, manganese, and vanadium.

This tool steel is particularly distinguished by its exceptional hardness of up to 60 HRC, providing excellent wear and abrasion resistance. Its tensile strength reaches an impressive 1,500 MPa, making D2 highly resistant to mechanical stress.

Additionally, D2 offers good heat resistance up to approximately 500 °C and is known for its durability. Material costs range from €80 to €160 per kilogram, placing it in the mid-range category.

However, D2 also has disadvantages: its corrosion resistance is low, meaning improper storage can promote rust formation. Furthermore, processing is demanding — both 3D printing and post-processing require specialized procedures, and welding is only possible with particular techniques and precautions.

The primary application of this cold-work tool steel is in the production of tools. It excels in cutting and stamping tools, punches, dies, and thread-rolling tools, where its high hardness and abrasion resistance are ideal.

D2 is also well-suited for precision tools that must withstand high mechanical loads. Thanks to its robustness and longevity, D2 is frequently used for series production of tools.

H13 is another high-alloy tool steel, but it differs from D2 by having a lower chromium content of approximately 5% and a reduced carbon content of around 0.4%. The alloy also contains molybdenum, silicon, vanadium, manganese, as well as small amounts of sulfur and phosphorus.

Compared to D2, H13 stands out for its higher heat resistance of up to 550 °C, making it well-suited for high-temperature applications. Its tensile strength is also impressively high, reaching up to 1,400 MPa.

H13 has a hardness of 54–56 HRC. While this does not quite reach the peak values of D2, it still provides very good protection against wear and abrasion. Unlike D2, H13 is less prone to rust, although it still does not exhibit outstanding corrosion resistance.

The processing challenges of H13 are similar to those of D2. Both 3D printing and post-processing are demanding, and welding is difficult due to the risk of distortion or cracking. With costs ranging from €120 to €250 per kilogram, H13 is significantly more expensive than D2.

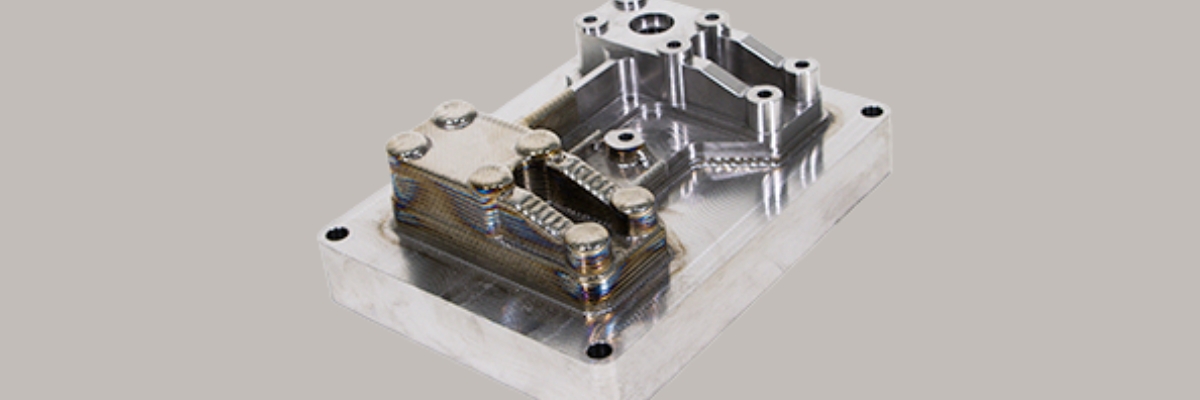

H13 is primarily used for tool production, with a focus on casting and die-casting tools, die and forging tools, as well as tools for hot forming.

Additionally, H13 is frequently employed in metalworking, where tools are subjected to high thermal and mechanical loads. In particular, the automotive industry values H13 for the production of high-performance tools.

In addition to steel-based alloys, which constitute the majority of metal 3D printing, there is now a wide range of specialty alloys suitable for additive manufacturing, offering significantly superior properties for specific applications.

In this section, we examine five different alloys — Ti-6Al-4V, Inconel 625, Inconel 718, copper, and CoCrMo — beginning with the material renowned for its outstanding strength-to-weight ratio.

Ti-6Al-4V, also known as Grade 5 titanium, is the most widely used titanium alloy in both conventional and additive manufacturing. It consists of approximately 90% titanium, around 6% aluminum, and about 4% vanadium, supplemented with small amounts of iron, oxygen, and carbon.

The alloy is particularly valued for its excellent strength-to-weight ratio. With a relatively low density of approximately 4.43 g/cm³, it achieves a typical tensile strength of 900–1,200 MPa, making it ideal for mechanically demanding components that require low weight.

In addition, Ti-6Al-4V offers high corrosion resistance against seawater and most acids, with the exception of nitric acid. It is biocompatible, has a moderate hardness of up to 38 HRC, and is easily weldable — though an oxygen-free environment should be maintained to prevent brittle areas.

However, the alloy has a limited heat resistance of around 400 °C, imposes high demands on 3D printing and post-processing, and is among the more expensive materials in metal 3D printing, with prices ranging from €250 to €500 per kilogram.

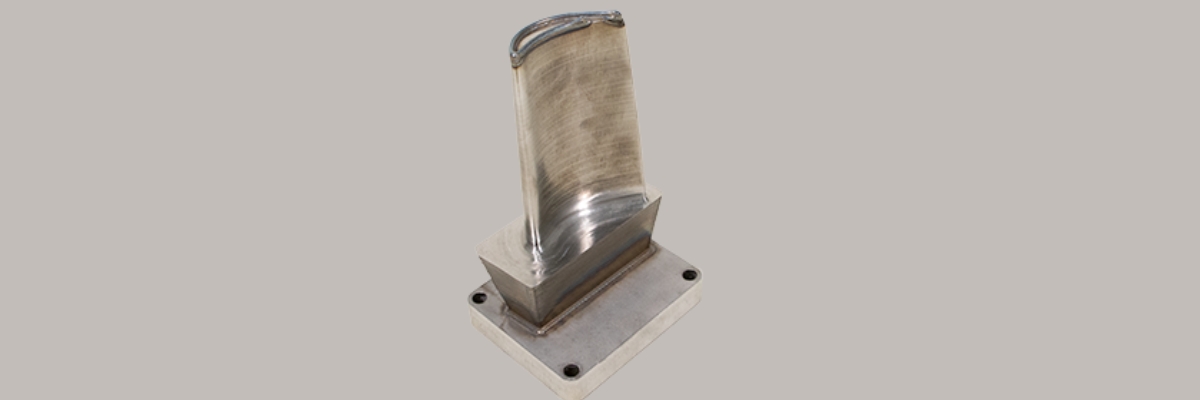

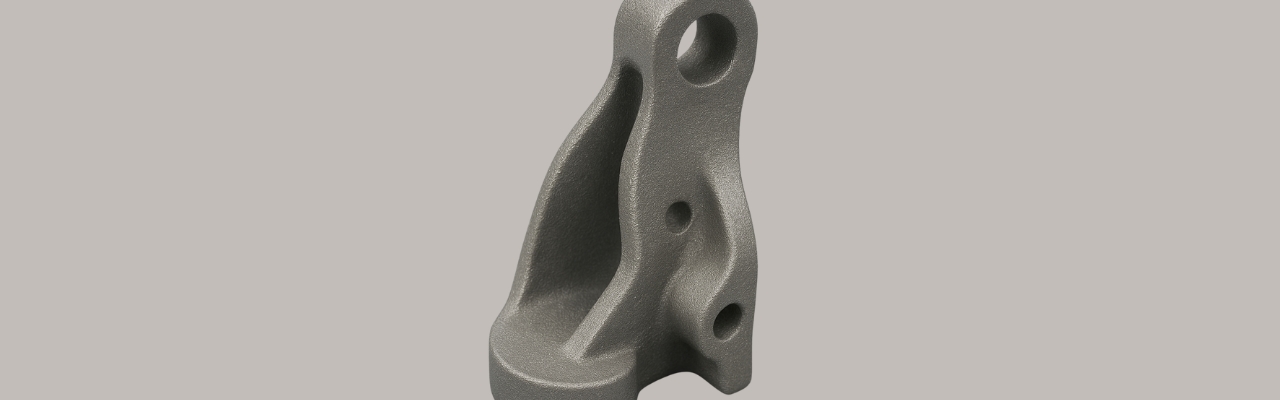

Thanks to its outstanding strength-to-weight ratio, Ti-6Al-4V is especially popular in the aerospace industry. Combined with the design freedom offered by 3D printing, it enables the production of lightweight yet durable components such as wing frames, fairings, fuselage structures, compressor blades, and landing gear parts.

Other industries also benefit from the properties of Ti-6Al-4V, including automotive, maritime, defense, energy, and the chemical and petrochemical sectors.

One of the two particularly popular nickel alloys in 3D printing is Inconel 625. The alloy consists of approximately 58% nickel, around 22% chromium, about 8% molybdenum, roughly 5% iron, approximately 4% niobium, and small amounts of other elements such as manganese, silicon, and carbon.

Inconel 625 is especially distinguished by its exceptional heat resistance of up to 980 °C. This is complemented by high oxidation resistance and a tensile strength of up to 1,100 MPa, making the material highly suitable for demanding applications.

Additionally, Inconel 625 offers excellent corrosion resistance even under extreme conditions, along with good formability and high fatigue strength, attributable to its molybdenum and niobium content. The material is non-magnetic at room temperature, has a hardness of approximately 35 HRC, is easily weldable, and is moderately priced at €80–200 per kilogram.

Compared to Ti-6Al-4V, Inconel 625 has a relatively high density of around 8.4 g/cm³, making it less suitable for weight-sensitive applications. Both 3D printing and post-processing are more demanding, with tool wear occurring more quickly during post-processing.

Inconel 625 is primarily used in the energy sector. In both conventional and nuclear power plants, it is employed for heat exchangers, control rods, piping, and boiler components. The alloy is also preferred on offshore oil and gas platforms due to its excellent corrosion resistance.

Other applications include the chemical and process industries, such as heat exchangers and pump components; welding technology, including welding wires and electrodes; and the maritime industry, for example in propellers and fittings.

Inconel 718 is the second nickel alloy widely used in additive manufacturing. Compared to Inconel 625, it contains slightly less nickel and chromium (approximately 53% and 19%, respectively) but a higher iron content of around 18%. The alloy is further supplemented with elements such as niobium, tantalum, molybdenum, titanium, and aluminum in smaller amounts.

The strength of Inconel 718 is particularly noteworthy. With a tensile strength of up to 1,400 MPa and an exceptional yield strength of 1,100 MPa, it significantly surpasses Inconel 625, which has a yield strength of approximately 700 MPa.

In addition, Inconel 718 offers excellent creep and fatigue resistance, even at elevated temperatures. Its heat resistance reaches up to 700 °C — slightly lower than Inconel 625, but more than sufficient for most high-temperature applications. Despite its high strength and moderate hardness of around 35 HRC (which can be increased to 50 HRC through aging), Inconel 718 can be effectively formed and welded using specialized processes.

The alloy has a relatively high density of approximately 8.19 g/cm³, making it less suitable for lightweight applications. Both 3D printing and post-processing are demanding, costs range from €120 to €250 per kilogram, and despite its good corrosion resistance, stress corrosion cracking may occur under chloride exposure.

Due to its ability to withstand both high and very low temperatures, Inconel 718 is especially in demand in the aerospace industry. It is used in rocket engines for components such as combustion chambers, turbine blades, and mounts.

Other application areas include oil and gas, aviation, automotive, chemical industry, maritime, and tool and mold making, where the specific properties of Inconel 718 are leveraged for demanding applications.

Copper is an extremely versatile metal that is gaining increasing importance in 3D printing. It can be used either in its pure form or in alloys such as bronze (copper-tin) and brass (copper-zinc). This article focuses on pure copper.

The growing significance of copper powder is primarily due to its outstanding conductivity properties. With a thermal conductivity of approximately 390–400 W/mK and an electrical conductivity of around 59.6 × 10⁶ S/m, copper ranks just behind silver among metals.

Additionally, copper exhibits antimicrobial properties, capable of killing harmful microorganisms, which is particularly relevant in medical technology. Although copper is generally corrosion-resistant due to the formation of a patina, corrosion can increase under certain conditions, such as environments with high humidity, saltwater, or specific aggressive chemicals.

Corrosion resistance can be significantly enhanced through alloying with tin.

The material is easily weldable and machinable and is relatively affordable, with prices ranging from €30 to €80 per kilogram.

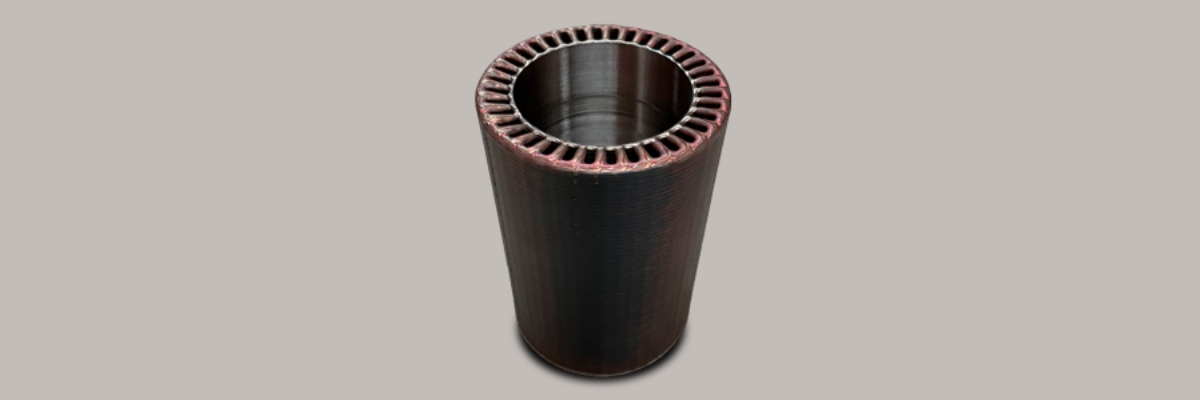

Due to its excellent electrical conductivity, copper is frequently used in electronics, for example in printed circuit boards, transformers, windings, and heat sinks, which can be manufactured additively.

Other applications include water and wastewater technology, where copper is used for pipes, valves, and fittings; the automotive industry, for example in radiator hoses and brake components; and the chemical industry, such as for catalysts and containers.

CoCrMo, standing for cobalt-chromium-molybdenum, is a relatively new alloy in 3D printing, though its range of applications is steadily expanding. In addition to its main constituents, CoCrMo contains small amounts of nickel, carbon, manganese, and silicon.

The alloy is distinguished by an exceptional combination of high hardness, corrosion resistance — including against bodily fluids — and biocompatibility. After appropriate heat treatment, CoCrMo can achieve hardness values of up to 55 HRC, ensuring no toxic reactions occur within the human body.

Moreover, the material offers high strength of around 1,200 MPa and a yield strength of up to 900 MPa. It also exhibits exceptional ductility at elevated ambient temperatures and heat resistance up to 1,000 °C. CoCrMo is diamagnetic and demonstrates outstanding wear resistance.

Processing CoCrMo in 3D printing is demanding and requires high-power lasers. Welding is not possible, and post-processing is challenging. At low temperatures, the material tends to be brittle and exhibits comparatively low ductility. With prices ranging from €150 to €350 per kilogram, it is among the more expensive materials.

Thanks to its biocompatibility and corrosion resistance to bodily fluids, CoCrMo has become well-established in medical technology. Combined with 3D printing, it enables patient-specific production of hip and knee prostheses, dental implants, dental bridges, and surgical instruments.

Additionally, CoCrMo’s high heat resistance opens up numerous applications in the automotive and aerospace industries, tool and mold making, chemical and process industries, as well as in welding technology.

Although metal 3D printing represents the newest form of additive manufacturing, a wide variety of materials is now available, each offering distinct properties and application areas, allowing their advantages to be leveraged across diverse industries.

I hope this article has provided a clear overview of the different metals, their strengths and weaknesses, and their ideal applications.

This concludes our blog series on materials in additive manufacturing. However, this blog will continue to provide regular updates on new developments in 3D printing — including innovative materials, advanced printing technologies, and exciting application possibilities.

Thank you for your interest, and we look forward to the next article!